To the Editor of the Bury Free Press

Sir - In answer to 'Enquirer', I beg to give him the following facts in connection with my personal knowledge of the Great Bustard -

In the year 1830, when a boy, I was staying at a farmhouse in Icklingham, a village eight miles to the north of Bury, and there, on a field adjoining the farm, I one day saw six of these magnificent birds grouped together. That same morning, but at some distance from this field, a nest of the Great Bustard was pointed out to me by a boy who was scaring birds off the rye. I observed and handled the eggs, but was induced to restrain my boyish desire of taking them by being made aware that Mr. Gwilt, upon whose estate the farm was situated, was a strict preserver of any Bustards that might happen to visit his domain.

In 1822, or thereabouts, my father purchased a female bird from a Mr Turner of Thetford, for three pounds. In 1824, Mr Turner wrote to say that he had just wounded and captured a fine male specimen, and that he had it alive. My father and I at once went over, and remember seeing the bird, a remarkably fine adult, in an outhouse. The fortunate possessor asked ten pounds for it; my father offered him seven, thinking, I believe, that no higher offer would be made. Here he was mistaken, for a gentleman at Windsor, hearing of the affair, at once secured the trophy. To the best of my knowledge that was the last bird captured in Suffolk or Norfolk. I should observe that on the same day, while driving to Thetford, we saw a large male Bustard in full flight over our heads. He pouch was plainly perceptible as it hung down, and it was doubtless filled with the water supply for a long journey. This circumstance, and the altitude, which was considerable, of the bird's flight, led us to imagine that it was taking its leave of Suffolk and Norfolk and perhaps of England.

The bird which I believe to have been the last of its kind killed in England was taken in Wiltshire, in 1833 (?) It was found by a plough boy on a turnip field, in a dying condition, having been wounded by a rifle shot. That bird was sent to Mr. Leadbeater's establishment, and I myself skinned and preserved it. Lovers of ornithology flocked to see it, and vied with each other in munificent offers for it possession. But the bird, albeit sixty pounds and upwards would readily have been given, was not for sale at any price. I may here say that a gentleman in this immediate neighbourhood, Mr. Newton, jun, late of Elvedon, offered ninety pounds. Shortly after I had skinned it a party of gentleman, consisting of Mr. Yarrell, Mr. Newton, and others, came to secure its breast bone, and were much disappointed upon hearing that the bird's body had inadvertently been consigned to a butcher's offal cart, and been conveyed to Greenwich as manure. Nothing daunted they personally repaired to Greenwich, and instituted an energetic search over the land where the offal had been thrown, but the body of the rare avis was not be found. Mr. Newton has since been to see me in Bury, and told me to be sure not to fail in acquainting him if I happened to meet with another Great Bustard. Previously to that he had written to me upon the subject, thinking possibly that I might have obtained the breast bone. I mention this fact to show how eagerly even the most minute and minor portions of rare birds are sought after by ornithologists with a genuine love of their pursuit. Mr. Gurney, late of Darlington, has a complete and ornate collection of breast bones, another gentleman, whom I know, possess a varied and beautiful series of skulls; and a third frequently writes to me for the trachea of scare birds. I shall be happy, should your correspondent,'Enquirer' care for them, to furnish him, if he will call upon me, with any other details of the date which I have here addressed.

Thanking you for allowing me so much space,

I remain, sir, yours truly

William Bilson

Natural History Workshop

Honey Hill, Bury, September 9th 1872

To the Editor

Sir - I see in your edition of last Saturday a reprint of a letter of the Rev. F O Morris in the Times. Allow me to correct an error of locality in Mr. Morris'; letter, and to claim for our county the honor he would bestow upon Cambridgeshire and Lincolnshire. A great bustard took up his abode in a piece of coleseed in my fen on January 4th. He occasionally visited other parts of the fen, but I do not think he was absent for a whole day from my field till February 24th. Through the kindness of Lord Lilford, I was enabled to turn out a female bustard on Thursday, February 10th, in the hope of inducing the noble stranger to remain with us, and if possible introducing them again to our county, their original home. Love at first sight was the result and the happy pair spent two days side by side in the coleseed - the male bird strutting round the hen, and flapping his wings like a Turkey cock. But, alas! The fearful weather on Sunday night and the day following proved too much for the tame bird, and on Tuesday she was found dead. The following Monday, Lord Lilford kindly sent another female; but the weather was so tempestuous I dared not turn her out. The next day the stranger departed. I have heard of him as far as Elvedon, the seat of his Highness Maharajah Duleep Singh, but since then no tidings have arrived. I trust, Sir, this short notice may induce any of your readers that he may visit to give him an hospitable reception. And I would add, Sir, not him only, but many others of those now too rare birds which occasionally visit us, some of which would doubles stop and breed with us if not hunted to death as soon as seen.

I am Sir, your obedient servant.

Feltwell, Norfolk, H M Upcher

The Great Bustard

Thy home is on the trackless wild,

Midst barren scenes and rude -

And never is they heart beguil'd

From thy blest solitude.

Thou hast no knowledge of the ways

Of birds familiar grown

With haunts of man, for all thy days

Are pass'd in regions lone.

Thy home has nought of sweet or fair -

No beauty crowns the lea;

And yet the desolation there

Is happiness to them!

To mingle with the feather'd throng

Thy bliss would not increase,

But mar the life whose joys belong

To solitude and peace.

. . . .

The crowd of men the sweets may court

Of city roar and rush -

But happier they who live Thought

In Nature's rural hush!

W F B

Although the great majority of English landowners encouraged, to their credit, the residence of this noble bird on their estates, and tried in every possible way to preserve it from destruction, there were yet some of these wealthy men who did just the opposite, and who, possessing no ornithological taste, and less respect for the opinion of bird-lovers, shot it down, whenever they had a chance, without a pang of compunction, and allowed their game-keepers and other servants to destroy it at pleasure. It is sad to think that in Suffolk and Norfolk, a district which was one of the great strongholds in Britain of this magnificent species, and where the bird was entitled, if anywhere, to protection, estate-owners were found who did not discountenance its deliberate, and often wanton destruction on their manors. For here it was that those who desired to preserve the Great Bustard from extinction in England had peculiar means of helping in so grant an object. The birds instinctively sough that district, that wild and desolate 'breck' land - Icklingham and Elvedent in Suffolk, and Thetford and Westacre in Norfolk - where no grain but rye was ever grown in the sandy soil, where a hedge was rarely seen, and where for miles around few traces could be discovered of man's presence; and where, in short, climate and soil and food and security held out to these birds the happiest advantages. To keep them attached to such a neighbourhood a little humouring of their habits on man's part was necessary. And with one or two exceptions the landowners did all in their power to preserve them, and to attract others to the district. And in this aim they would have succeeded far better, especially in Norfolk, if their efforts had been seconded by a certain large landowner who, however, persistently encouraged the Great Bustard's destruction on his estate, and who even allowed a man to kill the birds with a swivel gun. This fellow acquired quite a thirst for destroying Bustards, and to accomplish his aim the better he constructed masked batteries of large duck guns, so placed as to concentrate their fire upon a spot strewed with turnips. The guns forming his batteries had their triggers attached to a cord perhaps half a mile long, and the labourers on the estate were instructed by him to pull this cord wherever they saw the Bustards within range. On one occasion four duck guns of great size were fixed by this notorious Bustard-killer, and a week or so later a young man, when returning from Thetford to Wretham one wild and stormy day, saw, by the help of a pocket-telescope, no fewer than ten birds directly before the guns. He pulled the fatal cord and thus short seven of these large and magnificent birds at one discharge.

The female Bustard almost invariably laid her eggs in the winter-sown rye which, having been thrown broadcast on the land - as was in those days the universal custom - of course grew up in that weedy irregularity which delighted this bird's maternal soul. But when wheat began to take the place of rye a bad time was coming for the lady Bustards. For wheat was then sold at prices which would now make farmers jubilant, and it was important to use no more of the seed than could possibly be helped. At this juncture the drill was introduced, and weedy corn henceforth far less often vexed the eyes of the agriculturist, who however, it is to be feared, had very little sympathy for the lady Bustards! These latter were reduced to dire straits by reason of the unwonted freedom of the corn from noxious plants. Every nest was now pretty sure to be discovered, while the horse-hoe, which superseded manual labour in clearing the weeds, wrought terrible havoc among the eggs, either smashing them by the horses' feet or by the hose-blades. The system of weeding out corn in the spring says Mr. Stevenson has tended perhaps more than any other cause to the extinction of this bird. The young birds had thus little chance to grow up; security; and throughout the country the Great Bustard, owing to this and kindred causes, was rapidly becoming a name and a memory.

The food of this species consists of green corn, grasses and vegetables generally. They will kill and eat small mammalia, and from their partiality to marshy ground observes Yarrell, I have no doubt they also devour small reptiles.

As an edible bird the Great Bustard has for hundreds of years been held in high estimation, both in Britain and on the Continent; and at this day it is no unusual sight, in Spain and central Germany, to see this fowl exposed for sale in the market-places. To show the scarcity of the bird in England in 1818 I may mention that in that year a West-end poulterer sold a pair for twelve guineas. And in 1855 a male was captured in Wiltshire, for which Mr. Newton of Elvedon, offered twenty pounds. It sold ultimately for sixty pounds. It was of course wanted for preservation. While speaking of its gastronomic properties I may state that at a feast given in the Inner Temple Hall, October 16th 1565. The prices of various kinds of game were - Bustards 10s, Swans 10s, Cranes 10s, Pheasants 4s, Turkeys 4s, Capons 2s 6d, Pea chickens 2s., Partridges 1s 4d, Plovers 6d, Curlews 1s 6d, Godwits 2s 6d, Pigeons 1s 6d a dozen, Larks 8d a dozen, Snipes 2s a dozen, Woodcocks 7s 3d a dozen.

In old natural history records we read now and then of how Bustards were captured by greyhounds about Salisbury, on Newmarket Heath, and at other places; but in Suffolk and Norfolk at least there are no authentic memoranda of any such sport. And to suppose it was practiced anywhere would be equivalent of affirming that these birds cannot fly! It is true they will run some way before waking wing, but a Bustard can rise as light as a lark and its powers of flight, moreover, are marvellous. In Germany rifles are used in its pursuit, and so many are the devices which have to be practiced to get within short that the sport is said to be as good as stalking red deer in the Highlands. Bustard-shooting in Spain consists in driving round them in a cart and gradually diminishing the circle.

These birds have often been kept in confinement. A Mr. Hardy, who was a house surgeon to the Norwich Hospital from 1793 to 1826, kept Bustards many years, and succeeded in making them quite domestic. The Duke of Queensberry had three of these birds pinioned on his lawn at Newmarket, and my old friend Mr. Wastell of Risby, kept a pair in his garden for many years. The male was very bold, and at the same time very tame, and when I entered the garden it would approach me without any sign of fear. I remember it eating, among other things, mice and snails.

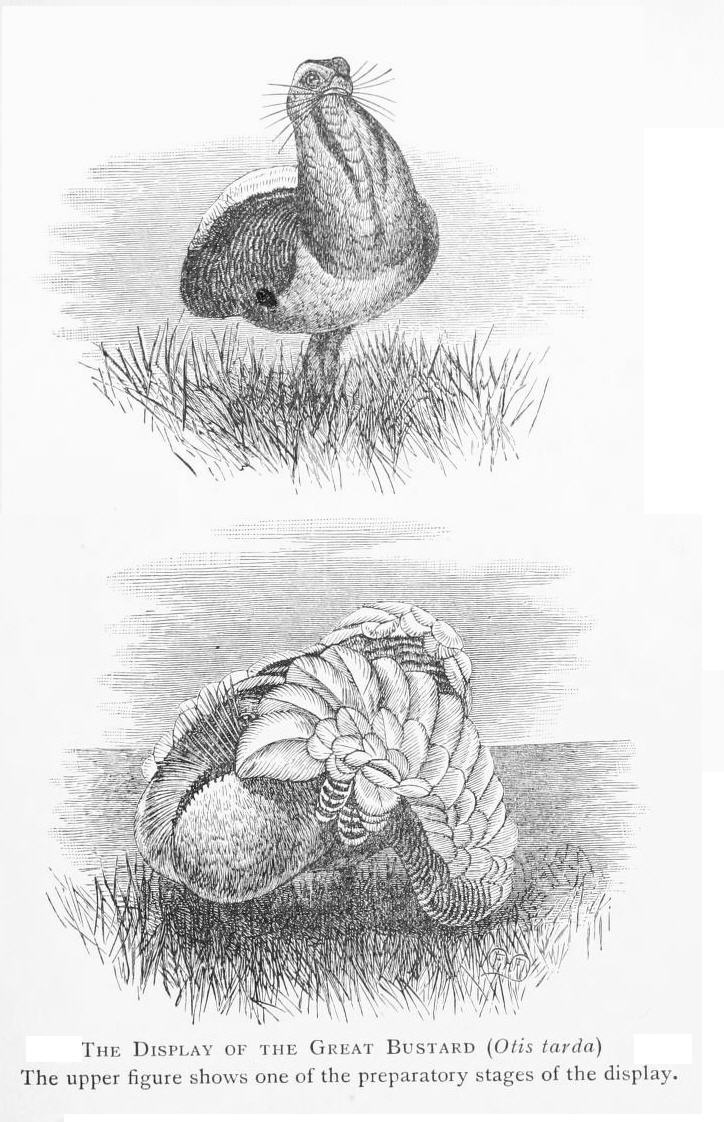

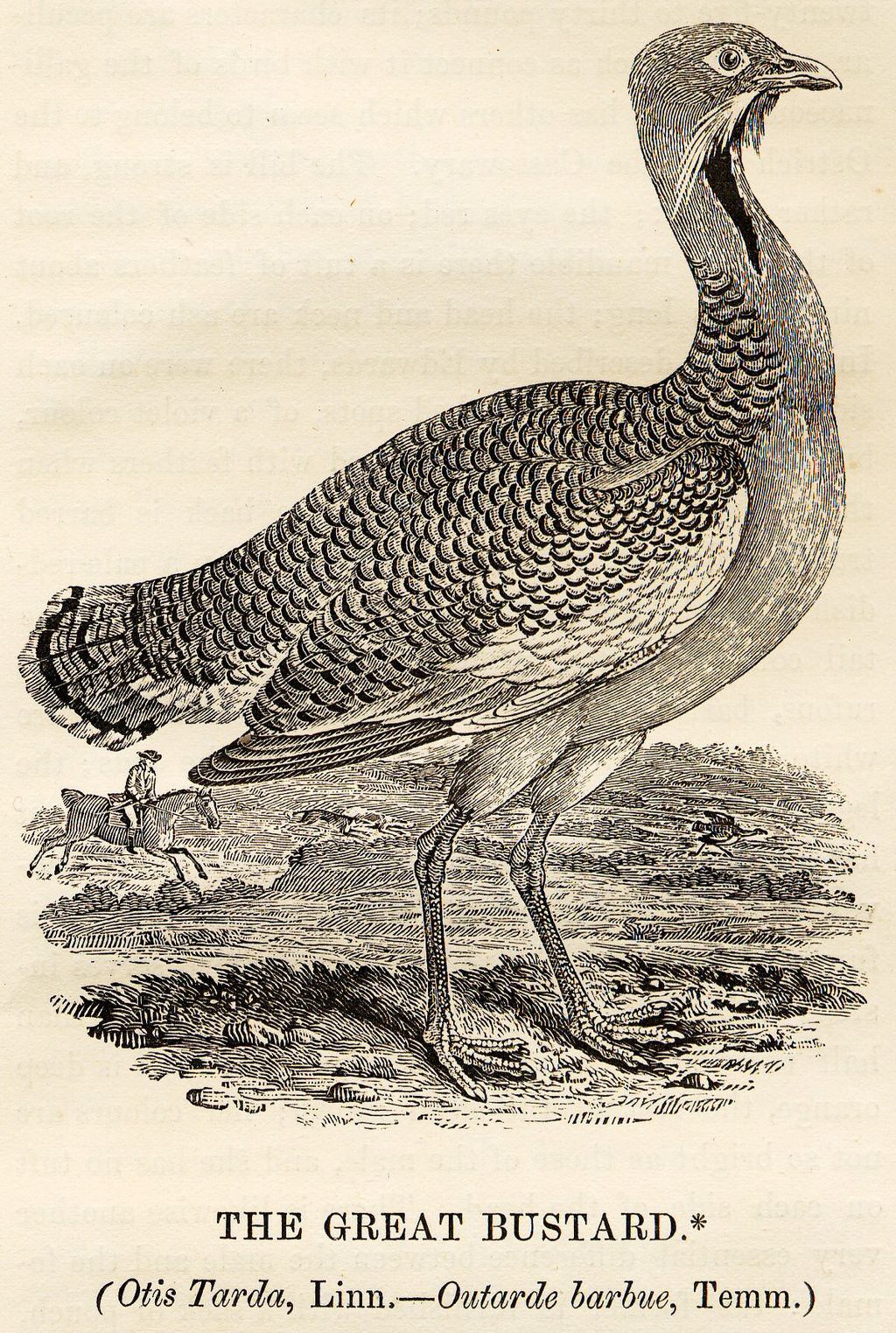

The male birds are very pugnacious in spring, and will fight to the death. A remarkable anatomical peculiarity in the male is a pouch or bag which, when full of water - and it will hold five or six pints - hangs from beneath the throat. But Yarrell doubts whether this pouch is really intended to hold water. At the time of its southern migration the Great Bustard becomes gregarious. The male is several years in arriving at its full growth, and till then is much like the female in plumage. In flight this bird works its wings somewhat after the manner of a Heron and hardly like a member of the Gallinaceous tribe. In shape it resembles the Stone Curlew, and its plumage is mingled greyish white, pale chestnut, and white. A male bird often weighs as much as 25 pounds. The whole length of male is 45 inches; of the female 36.

William Bilson, Naturalist, Mill Lane, Bury St Edmunds.

Sir Thomas Thornhill having disposed of Riddlesworth Hall, the celebrated collection of birds, including a very fine specimen of the Great Bustard, which was killed at Cavenham Heath in 1820, has been brought under the hammer. The curious 'gular pouch' which the male bird possesses, and the precise use of which has caused so much controversy amongst ornithologists, is thus referred to in a letter which Sir Thomas Browne wrote to his son in 1681: Yesterday I had a cock bustard sent mee from beyond Thetford. I never did see such a vast thick neck the crop was pulled out, butt as a turkey hath an odde large substance without, so had this within the inside of the

skinne, and the strongest and largest neck bone of any bird in England.

Notwithstanding its weighty proportions the testimony of practical ornithologists goes conclusively to prove that this powerful bird could rise as 'light as a lark'.

Concerning this bird, a correspondent writes: One of the important birds now extinct in this country is the Great Bustard, and considerable interest has been aroused amongst ornithologists in the neighbourhood by a Suffolk-bred specimen being offered for sale during last week at Riddleworth Hall, the property of Sir Thomas Thornhill. The Great Bustard is about the size of a goose, but somewhat longer in the leg and very much stronger on the wing. The breast is white, the back brown (speckled with black), and a spreading fan-like tail; the male measuring about 45 and the female 36 inches in length. They formerly frequented wild plains such as Newmarket Heath and Salisbury Plain, where they were little likely to be disturbed, and were known to breed, also at Westacre in Norfolk and Icklingham in Suffolk. But the gun of the so-called sportsman has altered all this, and now a very rare migratory specimen from the South of France or Spain is all that is ever seen. Only four specimens of true Norfolk or Suffolk bred Great Bustards are known to exist. Two are amongst the fine collection of birds in the Norwich Museum, one in a private collection in Norfolk, and the fourth is the one named above, which has just been sold. This was caught in a trap on the Cavenham Hall estate near Bury, about 70 years ago, and is therefore probably one of the Newmarket stock. It has been in Riddlesworth Halll over 30 years, is well stuffed, and in good condition still, but not a large specimen. It was the object of very spirited competition at the sale a day or two since, between representatives from Bury, Newmarket and Ipswich, being finally knocked down to Mr. Johnson of Bury at £46, but for whom it was purchased did not transpire. The Norwich Museum gave £25 for their last specimen. There are two Great Bustards in the Ipswich Museum, male and female, which are believed to have been shot on Salisbury Plain.

Bustards in East Anglia

Stories of 70 years ago

Mr C Gwilt of Duke Street, Adelphi, writing to the 'Standard', said that bustards were by no means uncommon in Norfolk and Suffolk some seventy years ago. In the course of an interesting letter he says:

I can entirely confirm the correctness of the statement that Icklingham in Suffolk, was one of their favourite haunts, as in my young days I often heard my later father allude to bustards having been seen there, and particularly to the last occasion of his seeing them. This was in the spring of 1827, when, as he was one day riding across Wether Hill Heath, at the upper part of his Icklingham property, he observed a flock of 13 bustards among the heather, or 'ling' as it is locally called. The birds were not at all shy, for my father was able to ride within 30 or 40 yards of the flock, some of the birds being occupied in 'dressing' their feathers as he quietly passed them.

At the period referred to the whole of the upper (northern) portion of Icklingham was an open heath of considerably over two thousand acres in extent, which latter was surrounded on the north, east, and west by extensive heaths in the parishes of Elvedon, North Stow and Eriswell. As the place where my father saw the birds was more than three miles distant from any dwelling, it is easy to understand the attraction which so open and secluded a locality had for them, as in those days the only persons who at all frequented their heaths were the shepherds, who, so far as Icklingham was concerned, had directions to avoid, if possible, disturbing the bustard if they saw any. I also learnt from my father that the immediate cause of the disappearance of bustards after 1827 was the detestably unsportsmanslike doings of 'some fellow from London' who about that time had either bought or rented an estate in Norfolk which had also been a favourite resort of the bustards, and who not only shot the birds, but also trapped them! My father said that the feeling in the county was so bitter at this wanton destruction of these rare and treasured birds, that there were many threats to either horsewhip or horsepond the offender, as every landowner on whose property bustards were seen did all he could to protect them. I may add that I have in my possession the remains of a bustard quill feather which was found on Wether Hill Heath about the year 1827.

As a further reminiscence of the past, I may, perhaps, be pardoned for making an allusion to the primitive methods which prevailed at Icklingham some hundred years ago in regard to sheep breeding. The custom was to keep the sheep nearly the whole of the year upon the open heaths, where they had to content themselves with such herbage as they could find in the shape of rough grass and the young shoots of the 'ling', and for the purpose of affording the sheep some shelter in bad weather, my great grandfather had had made across the entire upper heath, a distance of over two miles, four or five small plantations in the form of a crop, to that from whatever quarter the wind blew there would be to so describe it, a sheltering angle into which the sheep could be driven in severe weather. As each plantation was well basked in this also helped to break the wind, as well as the snow drifts, but during the winter hay used occasionally to be carted up to the shelters for the sheep, which were of the 'old Norfolk' breed, and very hardy. The villagers called these shelters the 'busks' being of course, a corruption of 'hursts'. In one of these 'husks' a pair of ravens had, when I was young, for many years made their nest, they being, I may remark, very scarce birds in Suffolk; and I will remember that as I was, one fine spring day, riding across Elvedon Heath, near the Icklingham boundary, I saw the pair sitting on the heath, not far from the green track I was following. As I approached them, they, singular to say, did not rise, but only hopped back a little way, and when I passed the pair they were only about thirty yards distant, and the sight I had of these two noble birds, with the sable plumage glistening in the sunshine, is to me a very pleasant memory. I never saw the ravens again, and, time having told heavily on the fine old Scotch fir trees which had so long been their home, they ultimately deserted it.

Bustards in Norfolk and Suffolk

Mr. Thomas Southwell, writing to the 'Standard' in reference to the extinction of the bustards, which formerly roved on the open country in the neighbourhood of Icklingham, on the borders of Norfolk and Suffolk, says:

Some correspondents do not fully discriminate between the indigenous British race of these birds, long extinct, and the foreign migrants which occasionally visit our shores. But I should like to remark, in the first place, that those interested in the subject will find an exhaustive history of the extinction of this noble bird as a British resident in the late Mr. Stevenson's Birds of Norfolk vol.II, pp. 1-42 and in the appendix to the third volume of the same work, p. 396.

The bustards formerly inhabiting Norfolk and the Suffolk borders were the last survivors of their kind in England, and outlived their brethren of Salisbury-plain and other localities. At the beginning of the present century there were two 'droves' one of which, numbering some 22 individuals, had its headquarters in the neighbourhood of Swaffham, Norfolk, the other composed of about an equal number of birds, frequenting the Suffolk border by Thetford and Icklingham; it seems not unlikely that stragglers belonging to the two droves occasionally commingled. Both of these flocks gradually diminished in number, the chief cause undoubtedly being the constant persecution with which they met but the planting of long belts of fir trees as shelters from the wind, which blows with great force over these tracts of open sandy heath, had much to do with rendering their former haunts unsuitable for these wild and cautious birds. The Icklingham drove became extinct in 1832, and the last of the Swaffham bustards was killed in 1838. Some years previous to this time all the males seem to have been killed, and the surviving females continued to drop their eggs in a purposeless sort of way without making any nest. Thenceforth, the great bustard ceased to exist in Britain as a native species, and those which have visited this country since at rare intervals have been foreign immigrants. Attempts have been made to re-introduce this grand bird, but I fear, from its wild nature and impatience of restraint, they will never prove successful.

In the Norwich Castle Museum there is a beautiful group of seven of these indigenous bustards, and the writer lately became possessed of the finest male bird he has yet seen, which was killed at Swaffham about the 1830. It seems not unlikely that this grand bird was the last male of the Swaffham drove. Recently I grieve to say, I have noticed the feathers of the bustard extensively used as hat plumes, and I fear that, should these become popular, even the wilds of Spain and Central Germany will soon see their last bustard done to death to meet the demands of this hateful trade.

As Lord Walsingham has already announced, an endeavor is being made to introduce the great bustard into Norfolk and Suffolk, the two counties in which it lingered longest before its final disappearance from the British Isles. This is an excellent enterprise, for of all the extinct species of British birds the Great Bustard has been the subject of the most regrets. Handsome in the russet and black of his plumage, and noble in his proportions - commonly he measured 8ft or more from tip to tip of his wings - he made a striking feature in local bird life when he ranged in droves about the Thetford and Swaffham 'brecks'. Early in the century he was well known on the wolds of Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, and to a lesser extent in some of the southern counties. By the fourth decade of the century he survived only in East Anglia. The last time he was seen in Suffolk was in the summer of 1832, and his last appearance in Norfolk was six years later. There is some controversy on the latter point, but according to the evidence set forth in Stevenson's Birds of Norfolk authenticity attaches to no date later than 1838. There is in the present day a more intelligent appreciation of bird life than at the beginning of the century, and hence the re-introduced specimens. To be procured most probably from Spain, may well escape mere wanton extermination. In the Thirties there was a gamekeeper named Turner who wrought wholesale destruction among the bustard droves round Thetford. He was accustomed to get within range of them by means a of a swivel gun mounted on a wheelbarrow and screened with boughs. Looking to the legal and other protective means which the landowners could set in motion, an atrocity of that sort, let us hope, would now be impossible. What the birds have most to fear is the operation in still greater degree of those very causes which led to their extinction in England seventy years ago. Being exceedingly shy, they choose for their nesting places wide open fields in which there is not cover for a lurking foe. Hence their ruin and decay is said to have been due to the introduction of agricultural machinery, by which their eggs were disclosed and often destroyed. Unhappily for the Great Bustard the field machinery of today is enormously greater than in the Twenties and Thirties.

…

The following letter (to Cambridge County Council) from Lord Walsingham to the Clerk with reference to the reintroduction of the Great Bustard in the Eastern Counties, which was referred by the Council to this committee, (General Purposes Committee) was read:

Merton Hall, Thetford, 25th November 1900

Sir - Having regard to the attempted re-introduction of the Great Bustard in our Eastern Counties, an endeavor is being made to induce the County Councils of Norfolk and Suffolk to recommend to the Home Secretary that a close time should be established for this bird throughout the year. If the members of the County Council for Cambridge should take the same view of the matter is would add great weight to application were it supported by a similar resolution on the part of your Council. Perhaps you will kindly mention the subject to your chairman and others. I may add for their information that the 15 birds successfully imported are now quartered in an enclosure of some 800 acres not far from the borders of your county, whence, after moulting, they will resume their full powers of flight and may be heard of at any time within the confine of your district. You will excuse me that the great interest I take in the success of this experiment has induced me to trouble you with this letter. I am, yours faithfully, Walsingham.

The committee agreed to recommend the Council to apply to the Home Secretary prohibiting the taking or killing of the Great Bustard throughout the Administrative County of Cambridge during the whole year on account of the rareness of the bird.

A lecture in connection with the Mutual Improvement Society on The Migration of the Birds of Norfolk was given on Monday in the Shirehall, Holt. Mr. C B Dack, who has more than a local name as a taxidermist, was the lecturer, and there was a crowded attendance. … Mr Dack went on to describe our now rarer visitors … and the great bustard. This latter noble bird was once common near Swaffham and on Thetford Warren. The last known wild bird was killed in 1838. Two or three years ago a gentle reared and turned off a number of these fine birds but they did not survive long, some being shot and other lost. The increase of population and the enclosing of common and heath lands have been among the causes contributing to their scarcity. From their habit of running when disturbed they have sometimes been called the 'English ostrich'.