Though flint is used everywhere in the Brecks as a building material, it is not stone. It even looks like stone, being a hard, shiny material, steely grey in colour and found in roundish nodules usually covered with a thick, white skin. It is actually a form of the mineral silica and comprises the remains of sea creatures, especially sponges and sea urchins, which collected on the seabed when the chalk was being formed about 70 million years ago.

Flint occurs in Breckland as beds in the chalk underlying the thin, sandy topsoil, or in glacial drift deposits on the surface of the land.

Within Thetford Forest are two of the earliest known archaeological sites in Britain yielding evidence of the use of flint tools: a palaeolithic lake-side living site near Mildenhall Warren Lodge, dated to 500,000 years ago and Lynford Quarry, dated to 60,000 years ago both sites where flint hand axes and waste flint tools have been found.

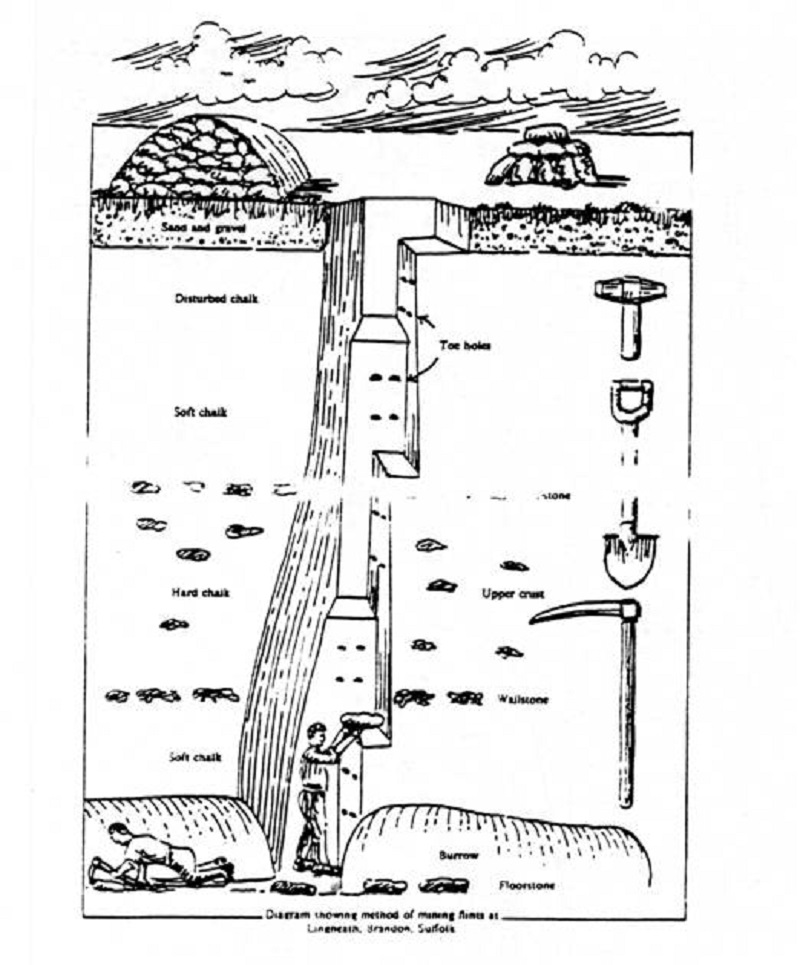

By the Neolithic period, c3500 to 2100BC, flint began to be used extensively and sourced from mines, including the known site at Grimes Graves only five miles from High Lodge. Grimes Graves has been recognised as one of the earliest industrial sites in the country, with over seven hundred flint-mining pits identified on the site. The name "Grimes" is thought to have come from the Saxon god Grim, whilst "grave" is the Saxon word for hollow.

Neolithic miners dug through the thin, sandy topsoil and soft upper chalk to construct a complex underground system of tunnels and galleries that gave them access to the high-quality black flint - known as floorstone flint - occurring in thin seams deep down in the chalk below. The miners used deer antler picks and shovels made from animal shoulder blades to remove approximately 70 per cent of the available floorstone.

Archaeologists have estimated that it would have taken 20 men about 100 days to dig a single shaft and then some 40 days of work by about six men to remove the flint. It has been further calculated that the miners would have used up to 150 antler picks in the process.

The flint was traded over a wide area and it is likely that the tools were perfected and finished at their final destination, rather than where they were mined. There is no current evidence of there having been any permanent domestic settlement at Grime's Graves, nor any firm indication of whether or not the mines were worked intermittently or as a full-time occupation.

There are flint pits around High Lodge which may be Neolithic. Certainly, Neolithic people were working with flints at High Lodge, leaving as evidence waste flakes and pot-boiler pebbles.

Very few written records have been discovered about the mining and uses of flint from the eleventh to the sixteenth centuries, though the church at Santon Downham is mostly constructed of flint and the warren lodges had flint walls.

By around 1600 flints were being used to create sparks to set off charges within flintlock guns and the best gunflints were made from the black flint found up to twelve metres below the surface in the area around Brandon (the same black flint layer extracted at Grimes Graves by Neolithic flint miners four thousand years earlier).

A key moment in the history of Brandon and flint was 16 June 1790, when Philip Hayward of Bury St Edmunds was awarded a government contract to deliver "100,000 flints of the best sort" to the Tower of London Arsenal. Subsequently, Brandon flintmmasters had the sole contract to supply the British Army with gunflints during the Napoleonic Wars (1789 - 1815).

In 1813 fourteen Brandon flint masters were contracted to supply 1,060,000 musket flints per month, worth about £18,000 annually and providing employment to 160 knappers and pit diggers or miners.

Flint Miners usually worked alone and rented an area of land on which to dig the pits to reach the black flint. Evidence of their work survives in the Forest as horseshoe shaped depressions, often surrounded by chalk and flint debris.

Each shaft was dug by a miner using a spade and single-pronged pick. The shafts – some of which were as much as 12 metres deep – were constructed in stages, with toe holes and a series of descending platforms cut in the chalk walls. In order to maximise the amount and quality of the flint he would be able to retrieve, the miner would consider the following when choosing the location to sink his next pit: he dryness and warmth of the location; the proximity to other workings and the depth to which he would need to dig to reach the layer of black flint.

“The average time taken to sink a pit of about thirty feet is three weeks,…, and some of the careful men commence a new shaft before an old pit is worked out in order to have some money coming in all the time.” (Skertchly, 1879).

The lumps of flint – known as nodules in their raw state – were hacked out and then hauled to the surface, ready for loading and delivery by cart to the knappers’ workshops in Brandon. Those not immediately transported were covered with branches of Scots pine as a protection against the weathering effects of sun and frost.

One cartload was equal to roughly a ton and a miner earned about 11 pence a jag, perhaps bringing to the surface three and a half jags in a six-day week.

The flint was delivered to the knappers in Brandon. They worked in sheds usually located behind dwellings, with many along the London and Thetford Roads and in the backyards of three public houses in the town.

The preparation of gunflints involved the three operations of quartering, flaking and knapping.

A knapper wore a protective leather pad on his left knee and a leather apron. He rested the nodule on the pad and used an iron hammer to tap it, gently severing it along a line of cleavage and so producing the quarters, from the square edges of which flakes could be struck. Three hundred gunflints could be produced in an hour by an experienced knapper.

Each different type of weapon required a different-sized gunflint. The largest gunflints were used for muskets, medium-sized ones for carbines or rifles and the smallest for pistols. The best "Brandon Blacks", used in the muskets and pistols, would last for about 50 shots.

The cores left after the gunflint flaking process were squared up and sold to builders; the remaining waste was used as ballast for roads and, later, railways.

During the course of the Napoleonic Wars, Brandon's reputation as the source of the best gun-flints made it the industry leader in Britain.

On 19th February 1813, the Board of Ordnance agreed at a meeting to contract Brandon flint masters to supply flints to the British Army for one year from 1st March in the following quotas:

"With every 8,000 flints, the contractors were to supply 1,000 carbine flints and 400 large pistol flints. No small pistol flints were required… No grey flints were to be received."

The Board also later offered the following contracts, but on more explicit terms:

As well as no grey coarse flints, these men were not to provide any white heeled ones either. (Forrest, 1983)

Herbert Field recounts: “Our working day began at 7am, but we had breaks for breakfast, dinner and tea, and seldom finished before 8pm. There was no flintwork on Mondays. Then I did gardening. On Saturdays we knapped only for the first hour. After that, there was ‘telling out’ – counting the flints knapped during the week. Father followed the old system. Seating himself in front of trays loaded with flints, he tipped them out in casts of five into tins by his legs, and totted up flints faster than anyone else I ever saw.”

The gunflints were then packed into tubs or sacks of five thousand to twenty thousand each for transportation to merchants in the major cities or ports.

Waste flints were used in the construction of roads and then for laying the track of the Great Eastern Railway in the 1840s.

There are a few written references to women active in the flintknapping industry. Elizabeth Grief was a flintmaster in the 1820s; Mary Snare was named as a manufacturer in the Brandon Gunflint Company and she, Fanny Shepperson and Mary Wright are listed as subscribers on the company's deed of covenant of 4 December 1837. Ann Clark and Sarah Giles are listed as flint mine ‘diggers’ at Lingheath in 1823, along with ‘Webber & Wife’.

The workshops were small one-storey buildings that were usually insufficiently ventilated, resulting in a dangerous build-up of dust inside. Many flint knappers suffered from silicosis, a lung disease caused by inhaling the dust.

W G Clarke reported how, in one workshop, seven out of eight knappers had died and that a father and his three sons had all died of the same complaint in four years. An obituary in the Thetford & Watton Times of 1 January 1916 recorded how, "The death of Mr Robert Field of 63 Thetford Road [Brandon] which occurred on the 20th December removed the last of the members of the family who have been engaged in the ancient industry of flint knapping for generations.

The British victory at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 brought peace, and with it a dramatic fall in orders for gunflints. The military supply contracts were not renewed and flintmasters cut the wages of their knappers to just above pauper level. As a result, many knappers were unable to support themselves and their families at a time of widespread economic depression.

By the early 1900s, there were less than twenty flint knappers and around six miners. Even so, these remaining knappers were still producing four million gunflints a year for despatch all over the world.

Brandon flints were still in use in Abyssinia in 1935 and even as late as 1950, 2,000 gunflints were being made each day in Brandon, for export mainly to Africa. By this point only a handful of knappers remained. The last of them, Fred Avery, died in 1996.

Lingheath, one of the main sites for the gunflint mining, was let as farmland, first of all to the War Agricultural Committee and then in 1948 to Charles Killingworth who recorded: “On arrival here, we had just forty-four acres fit for cultivation. The rest of the farm looked a wilderness of stones, chalk, trees and moss. It was overrun by rabbits. Scores of pits, each with heaps of stone and chalk round it, broke up the surface, tangled in parts by trees and scrub. You had to watch your step as you clambered around’.

Lingheath was just one of many sites for gunflint mining. A survey by Colin Pendleton, Suffolk County Council Sites & Monuments Officer, in 1996 showed ten sites of flint mining in the Brandon and Santon Downham areas including Broomhill; Elms Plantation and between Brandon and Elveden.

Flint-Mining had its own vocabulary:

Flint has also left a more general legacy in the English language:

To view the film about flint knapping Craftsmen: The Flintknappers 1949 Brandon, Suffolk, please go to the East Anglian Film Archive.

A major survey of flint mines was undertaken as part of the Flint in the Brecks project, part of the Breaking New Ground scheme. The results of this survey may be read on the Breckland Society website.

From the first-known industrial site, the Neolithic flint mines of Grime's Graves, through to the medieval churches and then to the miners and gunflint knappers of the 18th and 19th centuries, flint is undisputedly part of the history and heritage of High Lodge and Thetford Forest.

Audio Listening Post 3 on the Heritage Trail has more information about gunflint mining and overlooks the Lingheath site.